E-commerce and goods mobility

While goods movements are essential in sustaining urban life, transport also brings about negative side-effects.

Personal and goods mobility converges

The surge in online orders and the deliveries they bring forth unmistakably contribute to negative transport side-effects. To fully comprehend the impact of e-commerce on the urban environment, we should go beyond the one-sided focus on delivery operations. In fact, e-commerce presents a unique convergence of personal and goods mobility.

Last update February 18, 2022 by Heleen Buldeo Rai & Laetitia Dablanc.

The negative side-effects of transport have a local impact, such as traffic congestion, air pollution, noise nuisances and infrastructural damages. It is also responsible for a large share of greenhouse gas emissions, among which carbon dioxide or CO2, that have severe global implications.

Delivery success rates across different days of the week (Parcel Monitor, 2022).

When shopping goods online, consumers’ need to travel to stores is theoretically eliminated and delivery operations are created instead. Yet the relationship between personal mobility and goods mobility related to e-commerce is not that straightforward at all. Online consumers still visit physical stores for browsing, for researching and testing purposes or simply for social interactions. When online orders fail to be delivered at home or when an alternative location was selected during check-out, consumers still engage in collection trips. And when online orders do not live up to the expectation, are faulty or damaged, consumers still travel to stores or collection points to initiate a return process. These returns can create additional goods movements in turn. The graph illustrates delivery success rates around the world by Parcel Monitor (2022).

As such, it is paramount to consider both personal mobility (by consumers) and goods mobility (by retailers and logistics service providers). In analysing their “online consumption and mobility” survey among Parisians and New Yorkers, research bureau 6t (2018) found that understanding consumers’ purchase-related trips allows to better approach delivery practices’ changes and impacts. In turn, new delivery options change consumers’ activity paths as well.

In an increasingly urban world, the demand for both personal and goods mobility is expected to lead to a rapid growth of vehicle-kilometres. As shown below, ton-kilometres executed by goods vehicles are estimated to triple by 2050 compared to 2010.

Estimated growth of passenger and goods mobility (Arthur D. Little, 2015).

Sustainability impacts of e-commerce

The increasing volume of e-commerce transactions has significantly increased the number of new short-haul and last mile trips (Hooper & Murray, 2019). As such, e-commerce has created an explosion of goods transport for consumer deliveries in residential areas and office districts that were previously dominated by personal transport.

In the Paris region, freight demand generated 1 million B2B deliveries and collections per day in 2012, according to research group LAET. For B2C today, given the acceleration of e-commerce consumption linked to COVID-19, the figure is 500,000 to 600,000 per day (estimated from the global figure of one billion B2C parcels that would have been delivered in France in 2020). In Paris, the e-commerce frequency or the number of parcels ordered per household is estimated to be 30% higher than the national average (Oliver Wyman, 2021).

A study in Lyon by Gardrat et al. (2016) found that home deliveries amount to approximately 130,000 weekly movements, representing 17% of B2B goods movements in the city.

The French La Poste reports 10 million collections and deliveries per day in urban areas in France (Le Groupe La Poste, 2020).

European data collection by Roland Berger (2020) finds that, for every 1,000 urban inhabitants, 300 to 400 freight journeys are carried out. Deliveries in urban areas amount to 0.1 per person per day.

In the United States, research by Holguín-Veras et al. (2019) establishes that e-commerce adds 100 to 200 additional vehicle trips per day in large cities such as Los Angeles and New York, translating into nearly two additional trips per 100 people at a per capita level.

Also in the United States, household travel survey data of 2019 indicate 1 delivery per household in general and 1.35 deliveries in New York. We can see that there is still a "big city" effect, even if it is fading.

This interactive documentary or ‘doc-game’, created by the University of Lyon, allows to navigate the streets of Lyon and to discover various innovative initiatives in the urban logistics sector.

In France, a survey by ADEME (2020) demonstrates that the French make on average thirteen orders per month online. While e-commerce resulted in 505 million parcels in 2017 (FEVAD, 2018), a French report states that the number of parcels delivered in 2020 exceeds one billion or about 4 million parcels per day, with peaks of 10 million during festive periods such as the end of the year (Bon-Maury et al, 2021). In the city of Shenzhen in China, Xiao et al. (2021) estimate that over 350 parcels are handled per year per resident. In general however, detailed data on e-commerce related goods mobility in cities lacks. This problem is discussed at length in a review by Buldeo Rai and Dablanc (in review).

According to Airparif, heavy and light commercial vehicles account for 40% of nitrogen oxide emissions and 30% of carbon dioxide emissions (Dablanc et al., 2018). This amplifies urban mobility conflicts. On the one hand, logistics service providers try to minimise logistics costs, which are under pressure due to growing demand for services such as time-specific deliveries, temperature control and regulations. On the other hand, governments are assumed to seek maximisation of social welfare to reduce negative impacts of growing urban freight transport on our environment and quality of life. Among others, by making traffic restrictions such as in Paris by setting up vignettes (‘Crit’Air’) according to Euro engines standards. The mayor of Paris wants to ban diesel engines in the city in 2024 and gasoline engines in 2030.

Optimisation tools and new ITC technologies can help to optimise the fleet organisation in urban dense areas and thus limit the environmental impact of delivery trips. Hesse (2002) suggests that the expansion of e-commerce may lead to the atomisation of freight flows because rising carrier competition, increasing order flexibility require on-time delivery, often with less than a full truck load, at higher frequencies and with smaller vehicles. At the same time, Nemoto et al. (2001) estimated that the use of intelligent transport systems (or “ITS”) could make logistics operations more efficient by optimizing fleet management based on real-time traffic data. It is still expected that the use of ICT tools will help logistic companies optimise delivery routing and efficiency, governments to provide better transportation infrastructure and information and consumers to better organise their pick-up trips to avoid congestion (Cagliano et al., 2014).

Taniguchi and Kakimoto (2003) use modelling techniques of vehicle routing and scheduling with time windows and show that e-commerce can lead to more traffic in urban areas and negative impacts on the environment. When the e-commerce penetration rate reaches over 10%, however, the reduction in traffic for shopping by passenger cars overcomes the increase in home delivery truck traffic. Moreover, collection points and co-operative freight transport systems of home delivery companies and designating time windows by home delivery companies can substantially reduce total running times and NOx emissions. Visser et al. (2014) also highlight that consolidation of home deliveries will increase their efficiency and add more deliveries per trip, which will reduce the number of vehicle-kilometres per delivery.

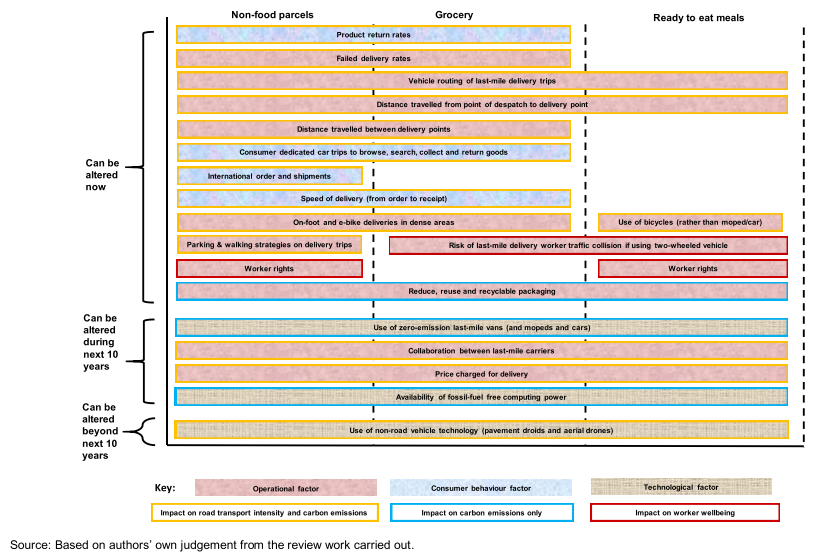

Based on a review of online shopping and last mile delivery practices in the United Kingdom, Piecyk et al., (2021) compiled a list of factors that lead to impacts, visualised in the illustration below.

References

6t (2018). Online Consumption and Mobility Practices: Crossing Views From Paris and NYC (Issue November). https://6-t.co/en/online-consumption-paris-nyc/

ADEME (2020). Profils des acheteurs en e-commerce - Synthèse des résultats de l’étude - mai 2020.

Arthur D. Little (2015). Urban Logistics: How to unlock value from last mile delivery for cities, transporters and retailers.

Bon-Maury, G., Fosse, J., Deketelaere-Hanna, M., Lambert, P., Vinçon, P., Constanso, V., Verzat, V., & Guérin, V. (2021). Pour un développement durable du commerce en ligne. https://www.contexte.com/article/environnement/info-contexte-ce-que-dit-le-rapport-gouvernemental-sur-les-impacts-du-commerce-en-ligne_128572.html

Buldeo Rai, H. & Dablanc, L. (2021). Treasure hunt in the e-commerce data jungle - A systematic literature review of the state of practice in urban logistics and e-commerce data. In review at Transport Reviews.

Cagliano, A. C., Gobbato, L., Tadei, R., & Perboli, G. (2014). ITS for e-grocery business: The simulation and optimization of Urban logistics project. Transportation Research Procedia, 3(July), 489–498.

Dablanc, L., Rouhier, J., Lazarevic, N., Klauenberg, J., Liu, Z., Koning, M., Kelli de Oliveira, L., Combes, F., Coulombel, N., Gardrat, M., Blanquart, C., Heitz, A., & Saskia Seidel. (2018). Deliverable 2.1 CITYLAB Observatory of Strategic Developments Impacting Urban Logistics.

FEVAD. (2018). Les chiffres clés 2018. Fédération e-commerce et vente à distance (FEVAD).

Gardrat, M., Toilier, F., Patier, D., & Routhier, J.-L. (2016). The impact of new practices for supplying households in urban goods movements: method and first results. An application for Lyon, France. VREF Conference on Urban Freight 2016. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01586947

Hesse, M. (2002). Shipping news: the implications of electronic commerce for logistics and freight transport. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 36(3), 211–240.

Holguín-Veras, J., Ramírez-Ríos, D., Kalahasthi, L., & Amaral, J. C. (2019). Freight and Service Activity Patterns in US Cities. TRB Annual Meeting.

Hooper, A., & Murray, D. (2019). E-Commerce Impacts on the Trucking Industry.

Le Groupe La Poste (2020). Le Groupe La Poste et La Caisse des Dépôts s’engagent ensemble dans la logistique urbaine en accelerant le developpement d’Urby. https://www.banquedesterritoires.fr/le-groupe-la-poste-et-la-caisse-des-depots-sengagent-ensemble-dans-la-logistique-urbaine-en

Parcel Monitor (2022). Top Delivery Success Rates Around the World. https://www.parcelmonitor.com/blog/top-delivery-success-rates-around-the-world/?utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=carriers_race&utm_content=gif

Nemoto, T., Visser, J., & Yoshimoto, R. (2001). Transport and Local Distribution: Impacts of Information and Communication Technology on Urban Logistics System. In The Impact of E-commerce on Transport (Issue June). http://www.oecd.org/sti/transport/roadtransportresearch/2668959.pdf

Oliver Wyman (2021). IS E-COMMERCE GOOD FOR EUROPE? Economic and environmental impact study. https://www.oliverwyman.com/our-expertise/insights/2021/apr/is-e-commerce-good-for-europe.html

Piecyk, M., Allen, J., Woodburn, A., & Cao, M. (2021). ONLINE SHOPPING AND LAST-MILE DELIVERIES. http://www.csrf.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/SRF_Online-Shopping-Full-Report-Final-Jan-2021.pdf

Roland Berger (2020). La logistique urbaine face aux défis économiques et environnementaux.

Taniguchi, E., & Kakimoto, Y. (2003). Effects of e-commerce on urban distribution and the environment.

Visser, J., Nemoto, T., & Browne, M. (2014). Home Delivery and the Impacts on Urban Freight Transport: A Review. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 125, 15–27.

Xiao, Z., Yuan, Q., Sun, Y., & Sun, X. (2021). New paradigm of logistics space reorganization: E-commerce, land use, and supply chain management. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 9(100300).