Instant delivery & quick commerce

The competition of e-commerce in urban areas is moving into the area of "instant deliveries", with retailers proposing deliveries in two hours, or less.

E-commerce’s tendency to ever faster deliveries

While the “modus operandi” developed by traditional logistics service providers in the parcel market is based on efficient consolidation and routing to achieve high drop densities, instant deliveries require a fundamentally new model.

Last update October 23rd, 2023 by Camille Horvath.

The concept of ‘instant deliveries’ entails all delivery services ordered via online platforms and carried out within two hours or less (Dablanc et al., 2017).

Delivery platforms sales growth (Ahuja et al., 2021).

The concept was first introduced by Dablanc et al. (2017) after being inspired by the online food ordering and delivery market. Worldwide, over 50% of all meal deliveries are managed by platforms and just under 50% by restaurants themselves (Statista, 2019). As the graph on the left shows, the growing food delivery business has spiked to new heights in most mature markets since COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdowns started in March 2020 (Ahuja et al., 2021).

Recent trends in quick commerce

A range of even faster companies emerged during the pandemic. The business model, coined “quick commerce”, proposes home delivery of groceries within twenty minutes. However, it's worth noting that several of quick commerce pure players, which thrived in 2021, no longer operate in several European countries since 2023.

Some of the pioneers, including the American Gopuff (2013) and the Turkish Getir (2015), kicked off the market almost a decade ago. Yet the pandemic years proved most fertile, launching dozens of companies around the globe, including Gorillas, Flink and JOKR (Schorung et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the transition from traditional to online shopping, leading to the growth of new e-consumption practices. However, this transition varies significantly from country to country.

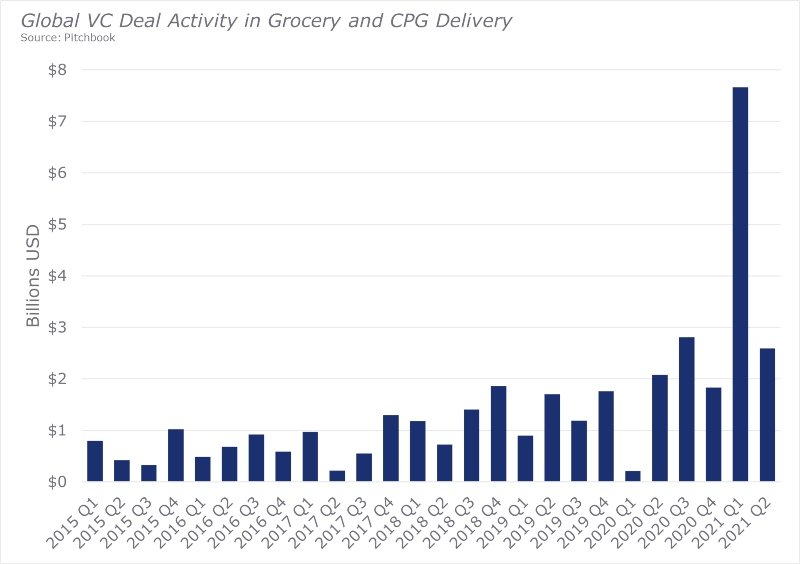

Global venture capital activity in grocery and consumer packaged goods (CPG) delivery, based on Pitchbook data (Delgado, 2021).

According to data from Mercatus/Incisiv, online food purchases represent 9.5% of overall food sales in the United States, a figure projected to exceed 20% by 2025-2026. In contrast, the rate was 8.3% in France in 2021 (Schorung, 2023). According to McKinsey's forecasts, the European online food market is expected to reach the 20% mark by 2030 (Delberghe et al., 2022). In terms of the proportion of consumers who have used online platforms to purchase food, the rate was 35.2% in Western Europe in 2021, compared to a whopping 88% in mainland China, according to data from Kantar Winning Omnichannel (Schorung, 2023).

Such platforms have raised significant funding, adding a range of new competitors to the fight for “share of stomach”. In just two years, the quick commerce industry raised over $8.9 billion in capital, $7.6 billion in 2021 alone. As such, it accounts for less than 1% of the total market but grows at a three-digit percent rate annually (Delberghe et al., 2022). An expensive business model seeking to monetize a sudden change in consumer behavior, quick commerce companies soon attracted significant sums of venture capital. Based on Pitchbook data, Delgado (2021) shows that venture capital-backed grocery delivery companies raised over $7 billion in funding throughout 2020. They exceeded that amount in the first quarter of 2021 alone. Based on Pitchbook data, a The Spoon article says that they raised $4 billion in 2021, or nine times more than the year before (Wolf, 2022).

However, the favorable winds behind quick commerce turned during 2022, as a considerable reduction in capital investment was witnessed in the sector (Schorung, 2023). Doubts regarding the viability of the industry, coupled with the mounting financial losses of all the firms operating in the sector and growing opposition from municipalities towards dark stores, contributed to this trend. Reports from the financial press repeatedly highlighted the questionable sustainability of the business model used by quick commerce firms, while the general press covered the various forms of resistance to the noise, pollution and disruption caused by dark stores, including opposition from local residents and municipalities (Hu, 2021). The figure below illustrates venture capital investments in quick commerce since 2018.

Capital invested (by venture capital) in quick commerce from 2018 to 2022 (source: Pitchbook Data, 2023; produced by Matthieu Schorung, 2023)

The quick commerce sector is experiencing a consolidation phase marked by bankruptcies, takeovers, and layoffs, as companies compete in a cash-burning elimination race fueled by massive fundraising efforts. The sector's high growth is enabled by strategies like "blitzscaling," which involves investing large amounts of capital in a short time to achieve rapid growth and outpace the competition. Companies like Gorillas, Flink, and Getir have raised billions of dollars to expand their operations, but they are also operating at a loss, with only a fraction of their hubs making a profit. The crisis in quick commerce has affected the entire food shopping and meal delivery sector, leading to layoffs and cutbacks at companies like DoorDash. Despite these challenges, many experts predict that new capital raising campaigns will take place in 2023, while survivors like Flink and Getir promise to turn a profit by the end of 2023 or in 2024.

Instant groceries is an important emerging market in cities. For several years now, Amazon Prime Now has allowed its Prime members to order from a selection of over 25,000 items and receive free delivery within two hours. In major cities around the world, one-hour delivery is also available for a fee (Dablanc et al., 2018). Retailers provide instant deliveries as well. For example, electronics retailer Fnac in France, offers two hours delivery by courier in Paris, Rennes, Lyon, Marseille, Strasbourg, Nantes, Toulouse, Nice and Lille. Sports retailer Decathlon proposes bike deliveries in eight Belgian cities, carried out by their own staff. Deliveries are same-day or instantly at a surcharge. Many instant delivery companies have been set up as local start-ups and are currently growing to regional markets. Examples in Paris include Urb-it and Stuart. The total number of active instant delivery couriers on the main delivery platforms in Paris (UberEats, Deliveroo, Stuart, Frichti, Glovo, etc.) was close to 50,000 in 2020 (Dablanc, 2021).

According to projections by Interact Analysis (2022), there are likely to be 45,000 dark stores worldwide by 2030, the majority of them outside Europe and North America. The quick commerce market in Europe is estimated to have been worth $25 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach $72 billion by 2025, according to Knowledge Ridge. In the United States, according to Grocery Dive (2021), the quick commerce market passed the $20 billion mark at the end of 2021 and should have grown to $38 billion by 2027. Quick commerce is a nascent sector that is mostly limited to large metropolitan areas, according to Fischer (2022). In a recent study on food e-commerce in Paris, London, and Geneva, the 6t research agency (2022) found that 69% of respondents who use such services receive their meals within 30 minutes, and 56% have their groceries delivered in less than an hour (64% in Paris, 50% in London, and 34% in Geneva).

Quick retailers dominate the same-day delivery segment for food products in Paris with a market share of 49%, according to a survey by Fox Intelligence by NielsenIQ. Overall in the Paris region, there are about 1.7 million deliveries and pick-ups per week (Dablanc et al., 2018), of which around 100,000 were instant deliveries in 2016. This resulted in an additional 100,000 pick-ups in the same area, as instant deliveries generally require a physical proximity between pick-up and delivery location. In 2016, instant deliveries may have represented about 12% of B2C related deliveries and pick-ups and 2.5% of total deliveries and pick-ups in the Paris region. However, quick commerce remains a marginal business in France, with a 2% channel usage rate per household, according to the Kantar Winning Omnichannel study (2022). There were 220 dark stores in France at the end of 2022, more than a third of them in Paris. Quick commerce is a growing niche, with a low penetration rate of 1.5% of French households, 3% in the Paris region, and 11.5% of Parisian households (Schorung, 2023). According to research conducted in 2016 by Dablanc et al., there were an estimated 0.2 instant deliveries per household per week in Paris. However, with the rapid growth of the delivery industry since then, it is safe to assume that this number has significantly increased.

Quick commerce business models and logistics

According to Schorung (2023), quick commerce operates using two main models : the "pure player" model, where a company owns warehouses called dark stores for storing products and preparing orders for delivery by couriers; and the "3-player" model, which involves a partnership between a sharing platform like UberEats and a quick commerce pure player. The latter owns dark stores that prepare orders placed by the marketplace, and deliveries are made by gig workers with service contracts. There's also a new model emerging where a customer and a marketplace are linked, and a personal shopper collects orders from selected locations. Additionally, some retailers collaborate with e-commerce pure players, such as Monoprix and Amazon's partnership in France, allowing online Monoprix orders to be delivered in under two hours in five cities, including Greater Paris.

Quick commerce business models (production: M. Schorung, 2023)

Traditional mass retail firms are adopting "2-player" models to compete with quick commerce players in the ultra-fast delivery segment. This model involves partnerships between a large food retail chain and a marketplace, with the retail chain providing supermarkets as storage and order picking locations, and managing the order picking service, while the marketplace provides the transportation service on the "ship-from-store" principle. In France, Carrefour has partnered with UberEats, and Monoprix has partnered with Deliveroo.

Carrefour and Uber Eats are expanding their collaboration beyond small purchases with the introduction of "Carrefour XL", a new service offering a range of 12 000 products. This service will be available in 20 cities, compared to the existing express delivery formula of 6 000 products in under 30 minutes, which has been available for three years and deployed in 1 200 stores and 200 cities. According to Les Echos (2023), the delivery of groceries is growing faster than the delivery of meals for Uber Eats because the market is less mature. Carrefour reports a business volume of 100 million euros generated through Uber Eats in 2021. Although the market is still young (at Carrefour, 80% of online orders are picked up through drive-throughs), it is expanding. In some Intermarché stores, for example, which work with Deliveroo (as does Carrefour for express delivery), orders through delivery apps can represent 1% to 2% of store sales.

Quick commerce is a rapidly evolving sector, which is still in the consolidation phase with multiple players : European (Getir-Gorillas, Flink-Cajoo, Glovo, Wolt), North American (Gopuff, JoKr, Instacart), Chinese (Meituan, Miss Fresh, ele.me), Indian (Swiggy, Faasos, Chaayos, Milkbasket), or South American (Rappi, Pedidos Ya, iFood). According to Schorung's (2023) research, while some markets, such as Germany, have already reached a consolidation phase with only two or three key players, many others are still in a state of constant change with ongoing mergers and withdrawals. In Paris, almost ten quick commerce companies, along with fast delivery companies and traditional mass retailers, were operating in 2021. Consolidation takes place through various methods, including takeovers, market withdrawals, layoffs, and partnerships. For example, Bam Courses expanded its catalog and shifted from a 30-minute to a 60-minute delivery service. Companies such as Gopuff, Zapp, and Gorillas have withdrawn from certain markets to reduce costs, while others have announced layoffs to adjust to the changing market.

In order to quickly capture markets and stifle competition, quick commerce companies have raised large amounts of funding to support their "blitzscaling" strategy. This approach involves opening numerous dark stores in different countries, partnering with large retailers and wholesalers, and aggressively advertising on all channels. However, this strategy has significant structural costs, primarily associated with dark stores, logistics, supplier costs, human resources, and marketing expenses. Currently, the quick commerce sector is facing less favorable lending conditions and a drying up of venture capital, which has led to a reduction in costs and a focus on developing new partnerships to expand markets. Despite these efforts, the business model of quick commerce has not been profitable so far, and companies need to achieve high order volumes per dark store and high average basket prices to reach break-even point. The main source of income for quick commerce comes from Gross Merchandise Volume, delivery costs, and retail media, while the retention rate and average basket size are also important indicators to consider.

The logistics of quick commerce are based primarily on dark stores. These are small premises located in densely populated areas (an estimate of 70,000 inhabitants within a radius of 1.5 km around each dark store is the gauge used by q-commerce operators), which serve as logistics bases for storing products, for preparing orders received via the quick merchant’s marketplace (mobile app), and the delivery of those orders. Schorung (2023) explains that dark stores are found in all types of ground level locations with access to a street (former non-profit premises, former shops or small supermarkets, disused garages, more rarely underground car parks). Their average surface area is between 200 and 300 m² (2,150 and 3,230 sq. ft), with products stored on shelves or in refrigerators. Outside the downtown area, dark stores, often located in the inner suburbs, have a larger surface area, from 300 to 500 m² (3,230 to 5,400 sq. ft), as was the case for Gopuff in the Paris region (Mariquivoi, 2022), and are often located in former production units or small warehouses. Dark stores primarily serve as small logistics bases – to provide their services, an average of nearly 2/3 of the surface area of a dark store is dedicated to product storage, shelving, and order preparation space.

Quick commerce companies use a partially vertically integrated supply chain model, where a central warehouse located on the city outskirts is used to supply dark stores in the city center and inner suburbs. The organization of quick commerce logistics is presented in the figure below. The central warehouse is usually supplied by third-party carriers and is a national hub for dark stores in other cities. Large food retailers like Casino and Carrefour have signed partnerships with quick commerce companies like Gorillas and Flink-Cajoo, giving the quick commerce companies access to a large supplier catalog and the benefit of the large group’s logistics system. In return, the quick commerce companies sell items from the retailers' own brands in their markets. However, other quick commerce companies like Getir and Gopuff have not signed exclusive agreements with major retailers and are supplied by several purchasing centers and independent traders.

Diagram of the organization of quick commerce logistics (information from interviews; produced by Matthieu Schorung, 2023)

Quick commerce companies rely mainly on in-house deliverers for the last-mile segment, who are assigned to specific dark stores. To ensure efficient service, mobile apps use a "geo-fencing" strategy that restricts orders to a specific area around a dark store. To reduce carbon emissions, delivery is made using carbon-free transportation modes such as bikes, electric scooters, and cargo bikes. However, this in-house delivery model leads to higher labor costs. To address this, some quick commerce companies have adopted a hybrid model that combines in-house couriers with gig workers from specialist companies like Uber Direct and Stuart, and to a lesser extent, third-party services for specific needs such as coursier.fr, Urb-E, or Olvo for cargo bikes.

Dark stores, which are retail spaces used solely for online order fulfilment, have become a source of concern for some municipalities due to their opportunistic location choices and potential impact on the local community.

A pressing issue revolves around concerns related to delivery-related nuisances. While Buldeo Rai et al. (2023) have shown that vehicles used in Paris are zero emissions, they do occupy curb space and contribute to congestion, occasionally causing noise disturbances as drivers await deliveries. These impacts have triggered reactions from urban authorities and communities within Paris, echoing similar responses in cities worldwide. For instance, Barcelona implemented a complete ban on dark stores in January 2023, while Amsterdam has limited their presence to specific business and industrial zones since 2022. In New York, City Councilwoman Gale Brewer is spearheading an effort to restrict dark stores in order to protect local bodegas and small neighborhood shops. However, ways of regulating quick commerce remain limited, and some companies are exploring ways to adapt to or circumvent these rules. This includes experimenting with click-and-collect services and incorporating collection points into dark stores. Other players are innovating by offering take-out fresh produce or making changes to their organization to develop good neighborly relations with local residents. For example, some dark stores now have transparent storefronts and welcome walk-in customers, while delivery vehicles are parked inside the store to limit local disturbance. In March 2023, the Council of State in France ruled that dark stores are warehouses under the urban planning code and are not intended for direct sales. Since July 2023, there has been a significant development in the quick commerce landscape in Paris, with major players such as Getir and Gorillas choosing to exit the market. These companies have reportedly entered into judicial liquidation in France. Getir has also withdrawn from Spain, Portugal, and Italy. In late 2022, Getir had acquired Gorillas, which, in turn, had purchased Frichti. Additionally, Flink, another German player, is undergoing judicial reorganization in France after acquiring Cajoo. The quick commerce sector in France has shrunk substantially, except for Deliveroo and Uber Eats, which have distinct operating models. Furthermore, GoPuff, an American company that entered the French market, has ceased its operations.

Major players in quick commerce

According to ETC Group (2022), the world’s biggest e-commerce food delivery companies are:

Meituan (China): Publicly-traded; 9,604 2020 revenue US$ millions for food delivery (total revenue: 16,637); so-called super app service company: food delivery (restaurant and grocery); group buying; movie tickets; hotel and travel booking (with ownership stake in hotels), crowdsourced healthcare (until 2021), pet care.

Deliveroo (UK): Publicly-traded; 5,263 2020 revenue US$ millions; restaurant food delivery; posted a loss of US$309 million in 2020. Amazon bought 16% of the company before its “disastrous” IPO, March 2021; Delivery Hero owns 5%. Launched Deliveroo Hop – grocery delivery – in London in 2021.

Uber Eats (subsidiary of Uber) / Postmates (USA): Publicly-traded; 3,904 2020 revenue US$ millions; Uber Eats acquired privately-held Postmates July 2020; divested Uber Eats India in exchange for 9.9% ownership stake in Zomato; completed acquisition of Cornershop Cayman – online grocery delivery in Chile and Mexico – in June 2021. Delivery segment reported operating loss in 2020.

Ele.me (China) “consolidated subsidiary” of Alibaba Group (acquired 2018): Publicly-traded; 3,593 2020 revenue US$ millions; delivery of prepared (restaurant) food, groceries; integrated with Koubei, Alibaba’s restaurant guide platform. In 2021, both became part of Alibaba’s new Lifestyle division, along with AutoNavi (mapping app) and Fliggy (travel app).

DoorDash (USA): Publicly-traded; 2,886 2020 revenue US$ millions; food and grocery delivery in the USA, Australia, Canada and Japan. Posted net loss of US$461 million in FY 2020.

Just Eat Takeaway / Grubhub (Netherlands): Publicly-traded; 2,850 2020 revenue US$ millions (includes Just Eat’s 2020 revenue; excludes Grubhub’s 2020 revenue of 1,800); delivers food and grocery. Takeaway bought Just Eat (UK) in 2020 and Grubhub (USA) in 2021; Delivery Hero owns 7.4%. Posted US$168 million loss for the FY.

Delivery Hero (Germany): Publicly-traded; 2,819 2020 revenue US$ millions; food, groceries, flowers, pharmaceuticals delivery; operations in 50 countries; in 2020, acquired Instashop (Middle East, North Africa), Honest Food Company GmbH (virtual kitchens, Central Europe) and Glovo’s Latin American food delivery operations; grocery delivery via “DMarts” in Middle East and Asia and via foodpanda in Germany; Prosus (tech investor giant) owns 27%. Posted US$1,020 million operating loss in 2020.

iFood (Brazil): Private Reporting; 494 2020 revenue US$ millions; food delivery in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia (joint venture with Delivery Hero), and Mexico. Company is a subsidiary of Movile (Brazil), but Just Eat Takeaway holds a 33.3% stake (Prosus is Movile’s majority shareholder); acquired SiteMercado (online grocery sales) in 2020.

Swiggy (India): Private; 375 2020 revenue US$ millions; subsidiary of Bundl Technologies Private Limited; prepared food (restaurant) delivery; cloud kitchen; grocery delivery via Swiggy Go; reported loss of US$508 million in 2020; Prosus (tech investor giant) holds 40% stake in Bundl Technologies.

Zomato (India) (Uber has 9.99% ownership stake): Publicly-traded; 370 2020 revenue US$ millions; prepared food (restaurant) delivery; reported loss of US$322 million; acquired Uber Eats India Jan. 2020; restaurant reservation booking; grocery delivery; owns 9.3% of Grofers (grocery delivery); supplier to restaurants via Zomato Hyperpure.

References

Ahuja, K., Chandra, V., Lord, V., & Peens, C. (2021). Ordering in: The rapid evolution of food delivery. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/ordering-in-the-rapid-evolution-of-food-delivery

Briard, C., Bertrand, P. (2023) Plus de produits livrés dans plus de villes : Carrefour et Uber Eats étoffent leur offre. Les Echos. https://www.lesechos.fr/industrie-services/conso-distribution/plus-de-produits-livres-dans-plus-de-villes-carrefour-et-uber-eats-etoffent-leur-offre-1935324#utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=re_8h&utm_content=20230417&xtor=EPR-5000-

Buldeo Rai H., Mariquivoi J., Schorung M., Dablanc L. (2023) Dark stores in the City of Light: Geographical and transportation impacts of ‘quick commerce’ in Paris, Research in Transportation Economics, Volume 100, 2023,101333,

Delberghe, C., Herbert, R., Laizet, F., Läubli, D., Nyssens, J.-A., Rastrollo, B., Vallöf, R., & Wachinger, T. (2022). Navigating the market headwinds – The State of Grocery Retail 2022: Europe. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-grocery-europe

Delgado, E. (2021, December 8). What’s Happening in the Explosive 10-Minute Delivery Space and What’s Next? McMillanDoolittle - Transforming Retail. https://www.mcmillandoolittle.com/whats-happening-in-the-explosive-10-minute-delivery-space-and-whats-next/

Dablanc, L., Morganti, E., Arvidsson, N., Woxenius, J., Browne, M., Saidi, N., Dablanc, L., Morganti, E., Arvidsson, N., & Woxenius, J. (2017). The rise of on-demand ‘ Instant Deliveries ’ in European cities. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal.

Dablanc, L., Rouhier, J., Lazarevic, N., Klauenberg, J., Liu, Z., Koning, M., Kelli de Oliveira, L., Combes, F., Coulombel, N., Gardrat, M., Blanquart, C., Heitz, A., & Saskia Seidel. (2018). Deliverable 2.1 CITYLAB Observatory of Strategic Developments Impacting Urban Logistics.

Dablanc, L., Aguilera, A., Krier, C., Adoue, F., & Louvet, N. (2021). Gig delivery workers in Paris. https://www.lvmt.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Instant-delivery-Paris-survey-2021.pdf

ETC Group (2022). FOODBARONS2022 Crisis Profiteering, Digitalization and Shifting Power. https://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/food-barons-2022-full_sectors-final_16_sept.pdf

Fischer, J. (2022). Appetite for rapid grocery delivery is growing around Europe. Knight Frank. https://www.knightfrank.com/research/article/2022-04-28-appetite-for-rapid-grocery-delivery-is-growing-around-europe

Hu, W. (2021). 15-Minute Grocery Delivery Has Come to N.Y.C. Not Everyone Is Happy. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/09/nyregion/online-grocery-delivery-nyc.html

Schorung, M. (2023) Quick commerce: will the disruption of the food retail industry happen? Investigating the quick commerce supply chain and the impacts of dark stores. Chaire Logistics City. https://www.lvmt.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Research-report-Quick-commerce-Schorung-mars-23-EN.pdf

Schorung, M., Buldeo Rai, H., & Dablanc, L. (2022, May 3). Flink, Getir, Cajoo… Les « dark stores » et le « quick commerce » remodèlent les grandes villes. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/flink-getir-cajoo-les-dark-stores-et-le-quick-commerce-remodelent-les-grandes-villes-182191

Statista (2019). Online food delivery - Worldwide. https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/online-food-delivery/worldwide

Wolf, M. (2022, June 21). The Case for 15-Minute Grocery Delivery is Questionable. So Why Did It Raise So Much Capital? The Spoon. https://thespoon.tech/the-case-for-15-minute-grocery-delivery-is-questionable-so-why-did-raise-so-much-capital/

6t. (2022). The impact of food e-commerce services on household lifestyles in Paris, London and Geneva. 6t-research office, Paris. https://www.6-t.co/article/la-pratique-du-e-commerce-alimentaire-a-paris-londres-et-geneve